Innovations: The Essence of Glass

With Meredith Price

January 18, 2007It all started with a rock. At the edge of the sea on a beach in Caesarea, Jeremy Langford, then 18, found an enormous, round sandstone covered in colored glass. "I was already dabbling in glass at the time, but this sandstone coated in iridescent glass, probably dating back to Roman times, was one of the most beautiful pieces I had ever seen, and it had a profound effect on me," says Langford. It was too heavy to pick up and carry, so Langford spent a few months dragging and burying the treasure until he could get it home.

Born in London to a family rooted in show business and the arts for generations, Langford was 16 when he moved here with his parents. "I couldn't stand it here and as soon as I passed my matriculation exams, I packed up and went back to England," he says, leaning on one of his own creations - a finely-crafted, oval conference table made entirely of clear glass. Back in London, Langford headed straight to a renowned glass artisan to learn the tricks of the trade. "I had been melting bottles and making things, so I showed him what I already had. He raised a bushy eyebrow and told me that if I could do that with no training, he couldn't wait to see what a classical education would do for me."

For the son of Barry Langford, one of the pioneers of Israel Television, moving around a lot was an integral part of life. "When my parents divorced, I finished my classical education in London and headed to South America with a backpack and a bag of tools." For what he calls "an extended period of time," he made his way around South America, supporting his travels through glass sculptures commissioned by various people he met along the way. "Back in the mid-'70s, the feudal system still ruled in South America, and there was invariably one rich ranch owner and then everyone else. I used to hang out in the local bar until I met someone who wanted a sculpture or work of glass art." After he returned from South America, Langford split his time between England and Israel. Interested in Kabbala, he says he started warming up to Israel. "I gave a lecture on Kabbala to a group of scientists at Ben-Gurion University. One of the scientists in quantum chemistry was interested in science as a pathway to deeper realms of existence. We hit it off immediately, which gave me an even better reason to like Israel," says Langford, who eventually married that scientist. Today, they have five children between 17 and 24. Langford credits his wife, Yael, not only with bringing him here, but getting him to settle down in one place - a difficult task to accomplish. They make their home in what Langford calls "the black belt of Ramat Gan," right on the border with Bnei Brak.

His studio, in an industrial section of Bnei Brak, is filled with glass sculptures, stained glass artwork and stacks of glass from all over the world. Spare shards lie in wooden crates outside, waiting to be reused or taken for a worthy cause. "My wife helped me set up this studio 20 years ago. Otherwise, I would still be a flighty artist with no direction," Langford says. Using her extensive knowledge of chemistry, she also helped him create a new technique to color glass. With more than 30 techniques in his repertoire, Langford puts his work into two distinct categories: architectural glass commissions for buildings, synagogues and private homes, and glass art and sculpture for museums and individuals. Although Langford has made hundreds of glass creations over the course of his career - from a wavy reception desk made entirely of stacked, green glass to enormous glass fountains - his masterpiece to date is a series of eight sculptures commissioned by the government and the Western Wall Heritage Foundation.

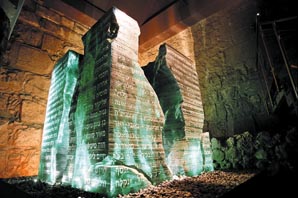

"The Kotel Project, which opened a few months ago in the visitors' center at the Western Wall in Jerusalem, is the first time a project of such magnitude, which combines 21st century, modern sculpture and technique in an ancient locale, has ever been done," he says. The chamber housing the main sculpture, Yearning to Zion, encapsulates 3,000 years of Jewish history. Suspended above a fully-preserved mikve dating back to the Second Temple, below what was originally used as a latrine by the Romans, it represents the symbolic return to the Promised Land and the inherent desire to return to the self. Constructed from thin pieces of stacked glass, it weighs 15 metric tons and is nine meters tall. "The layers upon layers of glass represent the layers of the long history of the Jewish people," says Langford. To place the sculptures in the ancient tunnel chambers, it was necessary to sculpt them in place. The eight sculptures required more than 150 tons of glass, three years of manufacturing and eight months of work on site to complete. "We probably could have done it faster, but we kept getting held up by archeological findings," says Langford.

Yearning to Zion, like the other sculptures in this exhibit, is carved with Hebrew lettering. "The Hebrew letters are actually names from different historic periods - from early biblical times up to the present day," Langford says. "They include ordinary citizens, rabbinical figures, Holocaust victims, the patriarchs - Abraham, Isaac, Jacob - and the Twelve Tribes." The glass medium was chosen both for its versatility and its aesthetic qualities. "One of the things I like most about glass is its relationship to light, its ability to both transmit and take in light," Langford says. Despite a vast range of artistic creations, he maintains a leitmotif of opposing forces‚ in his work. The ability to transform the hard, cold qualities of glass into warmth by playing with light dominates his work, and his interest in the dichotomy of forms influences his artistic choices. "Life is all about bringing opposites together," says Langford, his blue eyes alight. "I was given an incredible opportunity to work with such strongly opposing forces in the Kotel Project, and it's hard to imagine where to go after such a monumental project - historically, artistically and spiritually." Nevertheless, he seems to have a few ideas about future directions. Among them are a worldwide art project that forms a unified glass sculpture using the Internet and brain waves. "I have a deep, spiritual relationship with glass," Langford says. "An element that on the surface is seemingly hard and brittle appeals to me because I can transform it into something soft, sensuous and expressive."